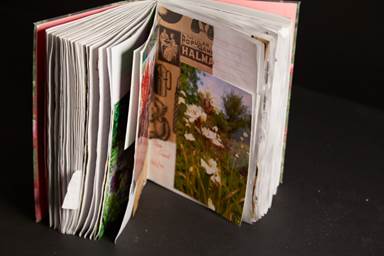

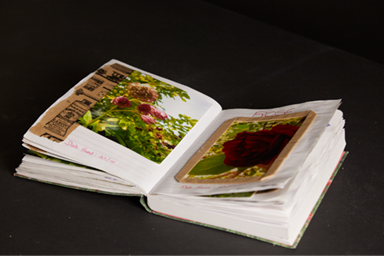

Green space is a place of calm and belonging, an escape from technology, an embrace of rustling leaves, a bird’s song and the scent of fresh earth. My love of nature was sparked by keeping a garden journal when we moved into our first home. Lovingly kept by the previous owner, Peggy, who, according to the neighbours was still pottering daily in the garden until the day before she sadly passed away. We moved into our new home in February, whilst the garden was sparse and dormant. People who knew Peggy told us that the garden would be an evolving gift throughout the year. It certainly was. I spent the whole of that year creating a garden journal, learning and understanding Peggy’s lifelong work – an incredibly fulfilling and grounding project. This experience made me wonder, have we always appreciated green space in architectural design, and does it alter overall wellbeing?

The importance of green spaces has evolved throughout history, formed by cultural values, technological growth, and design movements. ‘Green spaces such as domestic gardens, parks and woodlands provide a multitude of benefits to human urban populations, and a vital habitat for wildlife. By improving physical fitness and reducing depression, the presence of green spaces can enhance the health and wellbeing of people living and working in cities’ (Scott, 2015).

From ancient civilisations to modern cities, green spaces have been a fundamental element in architectural design. ‘Spending time in green spaces has been shown to produce levels and patterns of chemicals in the brain associated with low stress’ (Ward Thompson et al., 2012) ‘contact with nature is a basic human need rooted in evolutionary experiences’ (Gong et al., 2024)

Primitive culture placed a powerful emphasis on integrating nature into architecture. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon built around 600BC, is an example of how, even as far in history as the Mesopotamian period, humans had a belief that nature can heal and restore with a sense of belonging. ‘King Nebuchadrezzar II (reigned c. 605–c. 561 BCE), who built them to console his Median wife, Amytis, because she missed the mountains and greenery of her homeland.’ (The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, 2019). The gardens of Babylon are widely believed to be a gift, with the intention of improving the wellbeing of King Nebuchadrezzar’s wife who suffered from homesickness. Civilisation linked green spaces with improved mental health and medicinal qualities even in ancient times.

The Industrial Revolution in the 19th century created widespread urbanisation and a reduction of green spaces in favour of factories and housing. Conscious effects of the lack of green space led to movements that introduced parks in cities, such as Central Park in New York (built in 1857). ‘Its original purpose was to offer urban dwellers an experience of the countryside, a place to escape from the stresses of urban life and to commune with nature and fellow New Yorkers.’ (Central Park Conservancy, 2019)

Urbanisation continued in the 20th century. Rapid construction led to a significant decline in green spaces within cities. Concerns over pollution, climate change, and mental well-being have driven a renewed consideration around green space integration on Factory Land. ‘Around every factory or workplace there is some public land. It can include roof space and well as ground level sites. With care, thought and a little money, such spaces can be made more imaginative, more sacred in their own way’ (Palmer & Manning, 2000)

In 2025 cultural appreciation of green spaces is on the rise, shaping healthier and natural environments for future generations, supported by government initiatives. ‘Councils will be supported to put green infrastructure at the heart of their plans and priorities, improving the climate resilience of their places and enabling access for all’ (Heritage, 2024)

Giving someone the gift of nature, whether it’s flowers, plants, or an entire garden – carries deep significance to our human culture. From King Nanzebaars elaborate gift to his wife, to the inheritance of my garden, green space is more than just a beautiful gesture, it symbolises life, growth, and connection. Unlike material gifts, plants and green spaces evolve and thrive, reminding loved ones of your gesture over time. Architects should design our built environment with a commitment to thoughtful green space, improving the lives of inhabitants and giving the gift of nature to the next generation.

This blog is dedicated to Peggy; your work will always be treasured.

Bibliography

Central Park Conservancy. (2019, May 11). PARK HISTORY. Central Park Conservancy. https://www.centralparknyc.org/park-history

Gong, C., Yang, R., & Li, S. (2024). The role of urban green space in promoting health and well-being is related to nature connectedness and biodiversity: Evidence from a two-factor mixed-design experiment. Landscape and Urban Planning, 245(245), 105020–105020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2024.105020

Heritage, L. (2024, October 1). UK Councils invited to join and shape new initiative to improve access to nature and green space for millions of urban residents. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-councils-invited-to-join-and-shape-new-initiative-to-improve-access-to-nature-and-green-space-for-millions-of-urban-residents

Palmer, M., & Manning, D. (2000). Sacred Gardens. Piatkus Books.

Scott, C. (2015). UBoC UNITED BANK of CARBON. https://leaf.leeds.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/86/2015/10/LEAF_benefits_of_urban_green_space_2015_upd.pdf

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2019). Hanging Gardens of Babylon | History & Pictures. https://www.britannica.com/place/Hanging-Gardens-of-Babylon

Ward Thompson, C., Roe, J., Aspinall, P., Mitchell, R., Clow, A., & Miller, D. (2012). More green space is linked to less stress in deprived communities: Evidence from salivary cortisol patterns. Landscape and Urban Planning, 105(3), 221–229.

Figures

Figure 1: My Personal Garden Journal A. Personal Artefacts

Figure 2: My Personal Garden Journal B. Personal Artefacts

Figure 3: An artist’s impression of The Gardens of Babylon

https://www.worldhistory.org/Hanging_Gardens_of_Babylon

Figure 4: Central Park, New York https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/architect-new-yorks-central-park-incredibly-unexpected-legacy

Figure 5: My Personal Garden Journal C. Personal Artefacts