Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy undertook a bold experiment by designing New Gourna, an entire village aimed at curbing the ongoing looting of historic artifacts from ancient tombs. ‘The project was assigned by the Egypt government in 1946 and was built between 1946 to 1952. The purpose of the project is to rebuild a new village 3 kilometres away from the Old Gourna and relocate the residents in order to safeguard the pharaonic tombs that were embedded in the mountain of Gorn.’ (EARTH ARCHITECTURE, 2024)

Fathy’s hope was to create a sustainable, self-sufficient community based on traditional Egyptian architecture. Despite Fathy’s vision and passion, the project ultimately failed due to a cultural disconnect. ‘Unfortunately, the result was full of contradictions, highlighting the distance between the architect’s intentions and the interpretation of its intended residents.’ (Editors, 2023)

‘However attractive may have been the project of at last building a whole village, it was also somewhat daunting to be presented with fifty acres of virgin land and seven thousand Gournis who would have to create a new life for themselves there’ (Fathy, 2010).

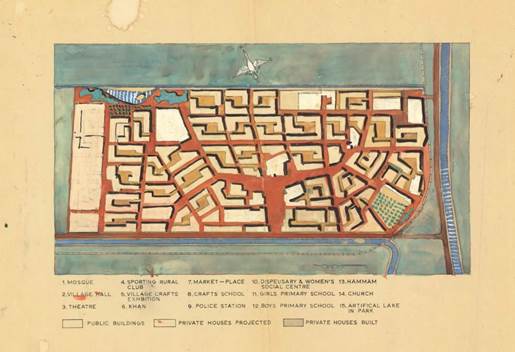

Hassan Fathy prioritised sustainability, affordability, and traditional methods in New Gourna, using mud-brick suited to Egypt’s climate. He designed Nubian-style domes, courtyards, and passive cooling for comfort without expensive materials. New Gourna was designed to be a thriving community, with opportunities of lifestyle choices alternative to looting ‘The public space was designed as the main street, the central square, and the buildings opened onto it: a Khan, a Mosque, a Theatre, a Village Hall’ (Taragan, 1999).

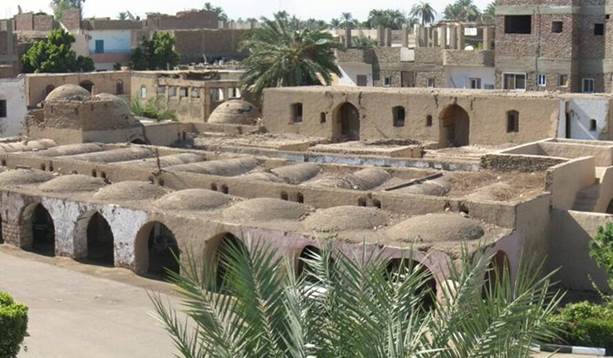

Insufficient understanding of cultural identity saw a disconnect between Fathy’s concept of mud-brick construction methods, domed roofs and courtyards, and villager’s perception that these structures were not desirable. While Fathy saw mud-brick as a sustainable and heritage driven material, the villagers associated it with old fashioned construction methods, poverty and rural life. The villagers of Old Gourna wanted homes that reflected their aspirations for modernity, preferring concrete construction and flat roofed homes, rather than domed roofs typically seen in tombs. ‘Even more curious for the future residents was the inclusion of domes in the house designs. As architectural forms, domes typically held a spiritual significance; they were associated with mosques and tombs, not homes. Using them in residential structures wasn’t just unusual, it was disconcerting’ (Editors, 2023). ‘Arches with bricks laid lengthways along the axis of the arch as described in the mastaba at Beit Khallaf, we used at most periods, especially for roofing small tombs’ (Clarke & Engelbach, 1990).

A cultural social structure misconception was another component leading to the failure of New Gourna. Fathy envisioned a well-planned, self-sufficient village with designated areas for communal gathering, craftwork, and trade. This was perceived as a rigid, inflexible, and imposed lifestyle. ‘What makes a city is a sharing between the civilization that inhabits it and the cultural qualities of its spaces’ (Atlas, 2020).

The villagers were used to a more organic, unplanned settlement style, where their homes and social networks were naturally evolving and developed informally over time. The imposed nature of the design felt restrictive rather than liberating.

Many Old Gourna residents made a living through tourism and the trade of artefacts from the tombs of Luxor and this was their main source of income. Moving to New Gourna caused unwanted economic disruption for the villagers. ‘The refusal of the Gourna community to red tape, failure to supply alternative sources of income, and other problems, presented a one-sided view, largely in the form of value judgments that did not reflect the open and more especially the hidden conflicts between the authorities and the villagers’ (Taragan, 1999).

Fathy envisioned the villagers of New Gourna thriving through handicrafts and agricultural work but failed to consider that they were not interested in such alternatives; residents were largely contented and settled with life, living above the ancient tombs.

Fathy was inspired by traditional Egyptian building techniques, but did not actively involve the villagers in the planning process, leading to a misjudgement of cultural design aspirations. He presumed that traditional forms would be automatically welcomed, and the villagers of Old Gourna would embrace his vision without considering their preferences. Ultimately, Fathy’s belief in simplicity and self-sufficiency clashed with the villagers’ desire for prestige and economic opportunity.

The New Gourna project highlights the crucial lesson that successful design must take into account cultural needs and desires, as well as the economic realities of the inhabitants. ‘These issues now, as at the time of construction half a century ago, revolve around the extremely important question of how to create a culturally and environmentally valid architecture that is sensitive to ethnic and regional traditions without allowing subjective values and images to intervene in the design process’ (Fathy & Steele, 1989).

Fathy’s work is admired for its sustainability and climate-conscious principles, but New Gourna stands as a reminder that architecture must be as much about culture as it is about design. Past achievements are not a guarantee of future success.

References:

Atlas, S. (2020, October 8). Hassan Fathy, Building With the People in New Gourna. Senses Atlas. https://www.sensesatlas.com/hassan-fathy-building-with-the-people-in-new-gourna/

Clarke, S., & Engelbach, R. (1990). Ancient Egyptian construction and architecture. Dover Publications.

Editors, T. (2023, August 8). Hassan Fathy and New Gourna. JSTOR Daily. https://daily.jstor.org/hassan-fathy-and-new-gourna/

Fathy, H. (2010). Architecture for the Poor. University of Chicago Press.

Fathy, H., & Steele, J. (1989). The Hassan Fathy collection : a catalogue of visual documents at the Aga Khan Award for architecture. The Aga Khan Trust For Culture.

New Gourna – Hassan Fathy – EARTH ARCHITECTURE. (2024, September 24). Eartharchitecture.org. https://eartharchitecture.org/?p=1138

Taragan, H. (1999). Architecture in Fact and Fiction: The Case of the New Gourna Village in Upper Egypt. Muqarnas, 16, 169. https://doi.org/10.2307/1523270

Figure references:

Figure 1 – Hassan Fathy (Right) in Cairo

https://www.sensesatlas.com/hassan-fathy-building-with-the-people-in-new-gourna

Figure 2 – Fathys Master Plan of Gourna Village

https://daily.jstor.org/hassan-fathy-and-new-gourna/

Figure 3 – New Gourna Village.

https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/666

Figure 4 – New Gourna Village Square

https://architectureindevelopment.org/project/30

Figure 5 – New Gourna Mosque

https://daily.jstor.org/hassan-fathy-and-new-gourna/

Figure 6 – Gourna village near to The Valley of The Kings

This is really interesting. I was not aware of Fathy’s work until I read this blog. I am somewhat surprised that we do not see more of these traditional building methodologies in modern architecture. Particularly when it comes to passive cooling, with the world continuing to warm up.

Keep up the great blog!